The Problem with Pet Food Marketing: What Every Pet Parent Should Know

- Katie A

- Oct 12, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 9

Understanding Pet Food Labels

You might think that if a pet food brand is pricey, recommended by a vet, or sold in a clinic, it must be high quality. But that’s not always true.

In creating the RECS 4 PETS app, I spoke with local pet-industry veterans. Many have over 20 years of experience. They confirmed what many pet owners suspect: the marketing around pet food is loosely regulated. Brand prestige doesn’t always equal ingredient quality.

Big brands often have a strong presence in veterinary offices, but that doesn’t guarantee better ingredients. Many of these brands invest heavily in veterinary schools, sponsorships, and “approved” studies. While this is legal, it can influence what veterinarians are familiar with or comfortable prescribing. Sometimes, better alternatives exist.

My Experience with Eddie’s Prescription Diet

When Eddie and I were in Las Vegas, he was diagnosed with struvite crystals. The vet insisted on a specific urinary-health formula available in the clinic. When I checked the ingredient panel, I was shocked:

The first two ingredients were whole-grain corn and brewer’s rice.

Brewer’s rice is a by-product: small, leftover fragments of processed white rice. It’s low in nutrient value and adds unnecessary carbohydrates. (For more on brewer’s rice, see FeedReal’s glossary: FeedReal)

While corn isn’t inherently bad, when it’s the first ingredient, it often means the formula is heavy in starchy carbohydrates. Read more on the American Kennel Club.

To me, it looked like filler before meaningful protein.

I asked the vet to prescribe Farmina, a different formula I found on Chewy with a cleaner ingredient list. She refused, stating she only prescribes the brand available in the clinic. Even after I pointed out that the vet’s recommended formula had reports of weight gain (and Eddie needed to lose weight), she held firm. Eventually, she agreed to use that same brand’s combined urinary + metabolic diet.

That formula’s first four ingredients were: brewer’s rice, corn gluten meal, powdered cellulose, and pea fiber — with protein only fifth. Imagine the daily calorie and nutrition load Eddie would get before ever seeing meaningful protein. He refused to eat it, and the cost was steep (~$58 per bag). The stress of transitioning, watching him refuse food, and worrying about his health was real.

I understand that prescription diets have clinical effects (in this case for urinary crystals), but why can’t a pet food company create something therapeutic using better ingredients?

Why the “First Ingredients” Matter

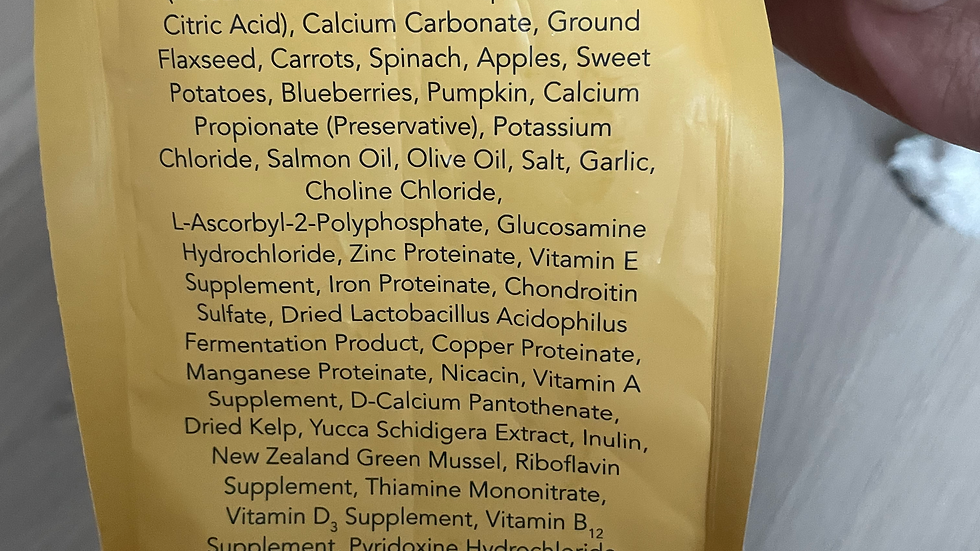

When you read a pet food label, ingredients are listed in descending order by weight. The heaviest components appear first, and the lightest (typically vitamins, minerals, flavorings) appear last. U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Because of this, the first few ingredients tell you a lot about what the bulk of the food is made of — meat, grain, filler, or by-products. AAFCO

According to Dr. Hannah Hart on PetMD by Chewy, a well-balanced dog food’s first five elements typically are:

A primary protein source

Carbohydrates

Fats

Vitamins

Minerals

If protein is buried deep in the list, there’s a good chance the food relies heavily on carbohydrate fillers or ambiguous “by-products.”

What Does the Law Say — and What It Doesn’t?

It’s crucial to recognize that “regulated” does not automatically mean “nutrient-dense.”

The FDA oversees that pet food is safe, manufactured under sanitary conditions, and properly labeled. It also requires that all ingredients be listed by weight, from most to least. U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The FDA reviews certain health claims (e.g., “low magnesium,” “urinary tract support,” “hairball control”) to ensure there’s some backing evidence. U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) establishes model nutritional standards and ingredient definitions. Though AAFCO itself is not a regulatory agency, many states adopt its standards within their laws. PetMD

Under AAFCO rules, ingredients must be listed using AAFCO-defined names (or common names), and aggregate or misleading terms like “animal protein products” are not allowed on pet food labels. Purina Institute

But here’s the catch: the law does not enforce a minimum “quality” grade for those ingredients (e.g., “premium,” “superfood,” “reserve”). Claims like “premium” or “gourmet” are largely marketing. Some boutique or smaller brands may be more transparent or careful, but there’s no guarantee simply due to brand prestige.

Why I Chose Lotus & Nature’s Select (and What to Look For)

Family-owned company in California, making food in small batches.

Operates its own cannery for wet food, giving the brand control over raw material processes.

They offer a senior formula optimized for urinary health (lower magnesium, phosphorus) — ideal for older dogs prone to stones.

Their small-bite kibble is perfect for dogs with dental issues (like Eddie, who’s missing many teeth). It’s smaller and crumbles easily in their mouth.

The first ingredient is chicken — a good sign that protein is prioritized.

Nature’s Select Plus (Texas-based)

Made in Texas and delivered locally (San Antonio to Austin region).

Ingredients are sourced from local farms and ranches.

Made in small batches, with formulas tailored for digestive needs or weight loss.

Uses chicken meal, which can allow for a higher protein concentration than raw muscle meat (nutrient-dense per weight).

No known recalls in over thirty years.

Eddie loved it immediately.

These brands caught my attention not just because of marketing. I evaluated the ingredient lists, company practices, and local availability.

How You Can Evaluate Pet Food (Without a PhD)

Read the first 4–5 ingredients.

If protein is buried deep, you’re probably getting filler calories.

Look for named proteins.

“Chicken meal,” “salmon meal,” “lamb liver” — not vague “animal protein products.”

Avoid by-products if possible.

By-products can be controversial (some good, some less desirable). If used, they should be clearly labeled (e.g., “chicken by-product meal”).

Check for “complete and balanced” statements.

Look for compliance with AAFCO standards or a life-stage statement.

Watch health claims carefully.

Terms like “premium,” “pro,” “superfood,” or “enhanced” are largely marketing. Only health claims regulated by the FDA (e.g., “urinary support”) must be backed by evidence. OnlineLabels

Don’t assume vet-office brand = superiority.

Budget, familiarity, and partnerships can drive which brands a vet carries — not always better ingredients.

Transition gradually — but flexibility matters.

Even high-quality food may not suit your pet’s taste or digestive tolerance. Always monitor for acceptance, digestion, and health.

Final Thoughts

Veterinary prescription brands are not inherently bad — many serve a medical role. But ingredients matter. It’s valid to ask whether they could formulate more thoughtfully.

I believe using a tool like the RECS 4 PETS app can empower pet owners with greater transparency. This enables them to make more informed food choices rather than relying solely on brand prestige or clinic availability.

Download the RECS 4 PETS app today on the App Store or Google Play for FREE.

Disclosure

Disclosure: Discussions of pet food ingredients and diets are based on personal research and experience. This is not veterinary or medical advice. All dietary decisions should be made in consultation with a licensed veterinarian who knows your pet’s specific health needs.

Get $10 off your first order of Nature's Select of $50 or more when you download the RECS 4 PETS app.

Comments